Oxidative phosphorylation

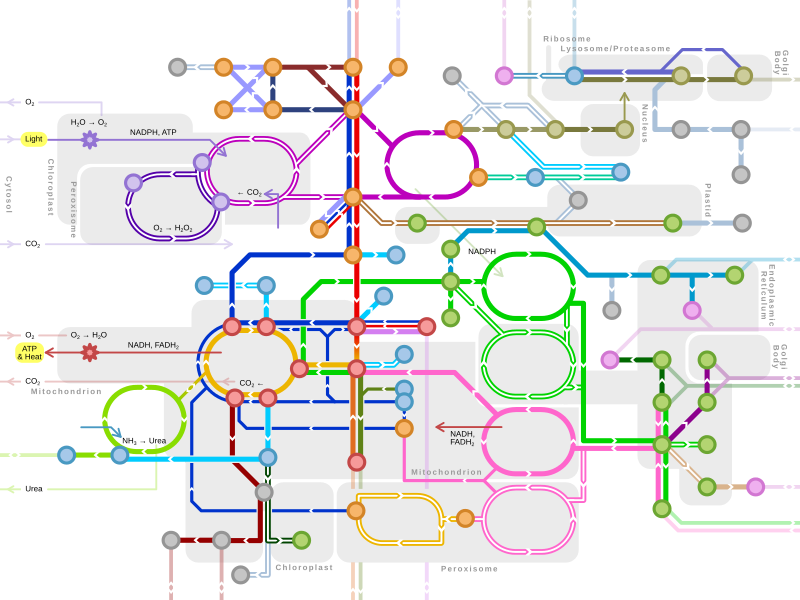

Oxidative phosphorylation (UK /ɒkˈsɪd.ə.tɪv/, US /ˈɑːk.sɪˌdeɪ.tɪv/ [1]) or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation is the metabolic pathway in which cells use enzymes to oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In eukaryotes, this takes place inside mitochondria. Almost all aerobic organisms carry out oxidative phosphorylation. This pathway is so pervasive because it releases more energy than alternative fermentation processes such as anaerobic glycolysis.

The energy stored in the chemical bonds of glucose is released by the cell in the citric acid cycle, producing carbon dioxide and the energetic electron donors NADH and FADH. Oxidative phosphorylation uses these molecules and O2 to produce ATP, which is used throughout the cell whenever energy is needed. During oxidative phosphorylation, electrons are transferred from the electron donors to a series of electron acceptors in a series of redox reactions ending in oxygen, whose reaction releases half of the total energy.[2]

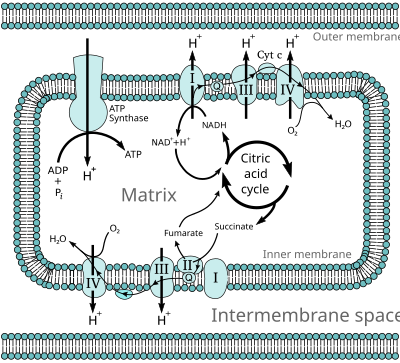

In eukaryotes, these redox reactions are catalyzed by a series of protein complexes within the inner membrane of the cell's mitochondria, whereas, in prokaryotes, these proteins are located in the cell's outer membrane. These linked sets of proteins are called the electron transport chain. In eukaryotes, five main protein complexes are involved, whereas in prokaryotes many different enzymes are present, using a variety of electron donors and acceptors.

The energy transferred by electrons flowing through this electron transport chain is used to transport protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane, in a process called electron transport. This generates potential energy in the form of a pH gradient and the resulting electrical potential across this membrane. This store of energy is tapped when protons flow back across the membrane and down the potential energy gradient, through a large enzyme called ATP synthase in a process called chemiosmosis. The ATP synthase uses the energy to transform adenosine diphosphate (ADP) into adenosine triphosphate, in a phosphorylation reaction. The reaction is driven by the proton flow, which forces the rotation of a part of the enzyme. The ATP synthase is a rotary mechanical motor.

Although oxidative phosphorylation is a vital part of metabolism, it produces reactive oxygen species such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, which lead to propagation of free radicals, damaging cells and contributing to disease and, possibly, aging and senescence. The enzymes carrying out this metabolic pathway are also the target of many drugs and poisons that inhibit their activities.

Chemiosmosis

[edit]Oxidative phosphorylation works by using energy-releasing chemical reactions to drive energy-requiring reactions. The two sets of reactions are said to be coupled. This means one cannot occur without the other. The chain of redox reactions driving the flow of electrons through the electron transport chain, from electron donors such as NADH to electron acceptors such as oxygen and hydrogen (protons), is an exergonic process – it releases energy, whereas the synthesis of ATP is an endergonic process, which requires an input of energy. Both the electron transport chain and the ATP synthase are embedded in a membrane, and energy is transferred from the electron transport chain to the ATP synthase by movements of protons across this membrane, in a process called chemiosmosis.[3] A current of protons is driven from the negative N-side of the membrane to the positive P-side through the proton-pumping enzymes of the electron transport chain. The movement of protons creates an electrochemical gradient across the membrane, is called the proton-motive force. It has two components: a difference in proton concentration (a H+ gradient, ΔpH) and a difference in electric potential, with the N-side having a negative charge.[4]

ATP synthase releases this stored energy by completing the circuit and allowing protons to flow down the electrochemical gradient, back to the N-side of the membrane.[5] The electrochemical gradient drives the rotation of part of the enzyme's structure and couples this motion to the synthesis of ATP.

The two components of the proton-motive force are thermodynamically equivalent: In mitochondria, the largest part of energy is provided by the potential; in alkaliphile bacteria the electrical energy even has to compensate for a counteracting inverse pH difference. Inversely, chloroplasts operate mainly on ΔpH. However, they also require a small membrane potential for the kinetics of ATP synthesis. In the case of the fusobacterium Propionigenium modestum it drives the counter-rotation of subunits a and c of the FO motor of ATP synthase.[4]

The amount of energy released by oxidative phosphorylation is high, compared with the amount produced by anaerobic fermentation. Glycolysis produces only 2 ATP molecules, but somewhere between 30 and 36 ATPs are produced by the oxidative phosphorylation of the 10 NADH and 2 succinate molecules made by converting one molecule of glucose to carbon dioxide and water,[6] while each cycle of beta oxidation of a fatty acid yields about 14 ATPs. These ATP yields are theoretical maximum values; in practice, some protons leak across the membrane, lowering the yield of ATP.[7]

Electron and proton transfer molecules

[edit]

The electron transport chain carries both protons and electrons, passing electrons from donors to acceptors, and transporting protons across a membrane. These processes use both soluble and protein-bound transfer molecules. In the mitochondria, electrons are transferred within the intermembrane space by the water-soluble electron transfer protein cytochrome c.[8] This carries only electrons, and these are transferred by the reduction and oxidation of an iron atom that the protein holds within a heme group in its structure. Cytochrome c is also found in some bacteria, where it is located within the periplasmic space.[9]

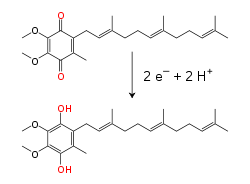

Within the inner mitochondrial membrane, the lipid-soluble electron carrier coenzyme Q10 (Q) carries both electrons and protons by a redox cycle.[10] This small benzoquinone molecule is very hydrophobic, so it diffuses freely within the membrane. When Q accepts two electrons and two protons, it becomes reduced to the ubiquinol form (QH2); when QH2 releases two electrons and two protons, it becomes oxidized back to the ubiquinone (Q) form. As a result, if two enzymes are arranged so that Q is reduced on one side of the membrane and QH2 oxidized on the other, ubiquinone will couple these reactions and shuttle protons across the membrane.[11] Some bacterial electron transport chains use different quinones, such as menaquinone, in addition to ubiquinone.[12]

Within proteins, electrons are transferred between flavin cofactors,[5][13] iron–sulfur clusters and cytochromes. There are several types of iron–sulfur cluster. The simplest kind found in the electron transfer chain consists of two iron atoms joined by two atoms of inorganic sulfur; these are called [2Fe–2S] clusters. The second kind, called [4Fe–4S], contains a cube of four iron atoms and four sulfur atoms. Each iron atom in these clusters is coordinated by an additional amino acid, usually by the sulfur atom of cysteine. Metal ion cofactors undergo redox reactions without binding or releasing protons, so in the electron transport chain they serve solely to transport electrons through proteins. Electrons move quite long distances through proteins by hopping along chains of these cofactors.[14] This occurs by quantum tunnelling, which is rapid over distances of less than 1.4×10−9 m.[15]

Eukaryotic electron transport chains

[edit]Many catabolic biochemical processes, such as glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and beta oxidation, produce the reduced coenzyme NADH. This coenzyme contains electrons that have a high transfer potential; in other words, they will release a large amount of energy upon oxidation. However, the cell does not release this energy all at once, as this would be an uncontrollable reaction. Instead, the electrons are removed from NADH and passed to oxygen through a series of enzymes that each release a small amount of the energy. This set of enzymes, consisting of complexes I through IV, is called the electron transport chain and is found in the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. Succinate is also oxidized by the electron transport chain, but feeds into the pathway at a different point.

In eukaryotes, the enzymes in this electron transport system use the energy released from O2 by NADH to pump protons across the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. This causes protons to build up in the intermembrane space, and generates an electrochemical gradient across the membrane. The energy stored in this potential is then used by ATP synthase to produce ATP. Oxidative phosphorylation in the eukaryotic mitochondrion is the best-understood example of this process. The mitochondrion is present in almost all eukaryotes, with the exception of anaerobic protozoa such as Trichomonas vaginalis that instead reduce protons to hydrogen in a remnant mitochondrion called a hydrogenosome.[16]

| Respiratory enzyme | Redox pair | Midpoint potential

(Volts) |

|---|---|---|

| NADH dehydrogenase | NAD+ / NADH | −0.32[17] |

| Succinate dehydrogenase | FMN or FAD / FMNH2 or FADH2 | −0.20[17] |

| Cytochrome bc1 complex | Coenzyme Q10ox / Coenzyme Q10red | +0.06[17] |

| Cytochrome bc1 complex | Cytochrome box / Cytochrome bred | +0.12[17] |

| Complex IV | Cytochrome cox / Cytochrome cred | +0.22[17] |

| Complex IV | Cytochrome aox / Cytochrome ared | +0.29[17] |

| Complex IV | O2 / HO− | +0.82[17] |

| Conditions: pH = 7[17] | ||

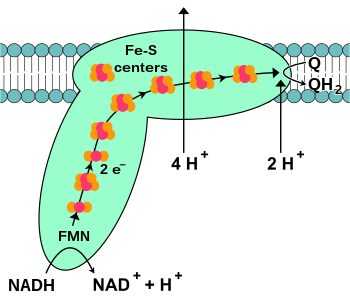

NADH-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase (complex I)

[edit]

NADH-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase, also known as NADH dehydrogenase or complex I, is the first protein in the electron transport chain.[18] Complex I is a giant enzyme with the mammalian complex I having 46 subunits and a molecular mass of about 1,000 kilodaltons (kDa).[19] The structure is known in detail only from a bacterium;[20][21] in most organisms the complex resembles a boot with a large "ball" poking out from the membrane into the mitochondrion.[22][23] The genes that encode the individual proteins are contained in both the cell nucleus and the mitochondrial genome, as is the case for many enzymes present in the mitochondrion.

The reaction that is catalyzed by this enzyme is the two electron oxidation of NADH by coenzyme Q10 or ubiquinone (represented as Q in the equation below), a lipid-soluble quinone that is found in the mitochondrion membrane:

| (1) |

The start of the reaction, and indeed of the entire electron chain, is the binding of a NADH molecule to complex I and the donation of two electrons. The electrons enter complex I via a prosthetic group attached to the complex, flavin mononucleotide (FMN). The addition of electrons to FMN converts it to its reduced form, FMNH2. The electrons are then transferred through a series of iron–sulfur clusters: the second kind of prosthetic group present in the complex.[20] There are both [2Fe–2S] and [4Fe–4S] iron–sulfur clusters in complex I.

As the electrons pass through this complex, four protons are pumped from the matrix into the intermembrane space. Exactly how this occurs is unclear, but it seems to involve conformational changes in complex I that cause the protein to bind protons on the N-side of the membrane and release them on the P-side of the membrane.[24] Finally, the electrons are transferred from the chain of iron–sulfur clusters to a ubiquinone molecule in the membrane.[18] Reduction of ubiquinone also contributes to the generation of a proton gradient, as two protons are taken up from the matrix as it is reduced to ubiquinol (QH2).

Succinate-Q oxidoreductase (complex II)

[edit]

Succinate-Q oxidoreductase, also known as complex II or succinate dehydrogenase, is a second entry point to the electron transport chain.[25] It is unusual because it is the only enzyme that is part of both the citric acid cycle and the electron transport chain. Complex II consists of four protein subunits and contains a bound flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor, iron–sulfur clusters, and a heme group that does not participate in electron transfer to coenzyme Q, but is believed to be important in decreasing production of reactive oxygen species.[26][27] It oxidizes succinate to fumarate and reduces ubiquinone. As this reaction releases less energy than the oxidation of NADH, complex II does not transport protons across the membrane and does not contribute to the proton gradient.

| (2) |

In some eukaryotes, such as the parasitic worm Ascaris suum, an enzyme similar to complex II, fumarate reductase (menaquinol:fumarate oxidoreductase, or QFR), operates in reverse to oxidize ubiquinol and reduce fumarate. This allows the worm to survive in the anaerobic environment of the large intestine, carrying out anaerobic oxidative phosphorylation with fumarate as the electron acceptor.[28] Another unconventional function of complex II is seen in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Here, the reversed action of complex II as an oxidase is important in regenerating ubiquinol, which the parasite uses in an unusual form of pyrimidine biosynthesis.[29]

Electron transfer flavoprotein-Q oxidoreductase

[edit]Electron transfer flavoprotein-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF-Q oxidoreductase), also known as electron transferring-flavoprotein dehydrogenase, is a third entry point to the electron transport chain. It is an enzyme that accepts electrons from electron-transferring flavoprotein in the mitochondrial matrix, and uses these electrons to reduce ubiquinone.[30] This enzyme contains a flavin and a [4Fe–4S] cluster, but, unlike the other respiratory complexes, it attaches to the surface of the membrane and does not cross the lipid bilayer.[31]

| (3) |

In mammals, this metabolic pathway is important in beta oxidation of fatty acids and catabolism of amino acids and choline, as it accepts electrons from multiple acetyl-CoA dehydrogenases.[32][33] In plants, ETF-Q oxidoreductase is also important in the metabolic responses that allow survival in extended periods of darkness.[34]

Q-cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complex III)

[edit]

Q-cytochrome c oxidoreductase is also known as cytochrome c reductase, cytochrome bc1 complex, or simply complex III.[35][36] In mammals, this enzyme is a dimer, with each subunit complex containing 11 protein subunits, an [2Fe-2S] iron–sulfur cluster and three cytochromes: one cytochrome c1 and two b cytochromes.[37] A cytochrome is a kind of electron-transferring protein that contains at least one heme group. The iron atoms inside complex III's heme groups alternate between a reduced ferrous (+2) and oxidized ferric (+3) state as the electrons are transferred through the protein.

The reaction catalyzed by complex III is the oxidation of one molecule of ubiquinol and the reduction of two molecules of cytochrome c, a heme protein loosely associated with the mitochondrion. Unlike coenzyme Q, which carries two electrons, cytochrome c carries only one electron.

| (4) |

As only one of the electrons can be transferred from the QH2 donor to a cytochrome c acceptor at a time, the reaction mechanism of complex III is more elaborate than those of the other respiratory complexes, and occurs in two steps called the Q cycle.[38] In the first step, the enzyme binds three substrates, first, QH2, which is then oxidized, with one electron being passed to the second substrate, cytochrome c. The two protons released from QH2 pass into the intermembrane space. The third substrate is Q, which accepts the second electron from the QH2 and is reduced to Q.−, which is the ubisemiquinone free radical. The first two substrates are released, but this ubisemiquinone intermediate remains bound. In the second step, a second molecule of QH2 is bound and again passes its first electron to a cytochrome c acceptor. The second electron is passed to the bound ubisemiquinone, reducing it to QH2 as it gains two protons from the mitochondrial matrix. This QH2 is then released from the enzyme.[39]

As coenzyme Q is reduced to ubiquinol on the inner side of the membrane and oxidized to ubiquinone on the other, a net transfer of protons across the membrane occurs, adding to the proton gradient.[5] The rather complex two-step mechanism by which this occurs is important, as it increases the efficiency of proton transfer. If, instead of the Q cycle, one molecule of QH2 were used to directly reduce two molecules of cytochrome c, the efficiency would be halved, with only one proton transferred per cytochrome c reduced.[5]

Cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV)

[edit]

Cytochrome c oxidase, also known as complex IV, is the final protein complex in the electron transport chain.[40] The mammalian enzyme has an extremely complicated structure and contains 13 subunits, two heme groups, as well as multiple metal ion cofactors – in all, three atoms of copper, one of magnesium and one of zinc.[41]

This enzyme mediates the final reaction in the electron transport chain and transfers electrons to oxygen and hydrogen (protons), while pumping protons across the membrane.[42] The final electron acceptor oxygen is reduced to water in this step. Both the direct pumping of protons and the consumption of matrix protons in the reduction of oxygen contribute to the proton gradient. The reaction catalyzed is the oxidation of cytochrome c and the reduction of oxygen:

| (5) |

Alternative reductases and oxidases

[edit]Many eukaryotic organisms have electron transport chains that differ from the much-studied mammalian enzymes described above. For example, plants have alternative NADH oxidases, which oxidize NADH in the cytosol rather than in the mitochondrial matrix, and pass these electrons to the ubiquinone pool.[43] These enzymes do not transport protons, and, therefore, reduce ubiquinone without altering the electrochemical gradient across the inner membrane.[44]

Another example of a divergent electron transport chain is the alternative oxidase, which is found in plants, as well as some fungi, protists, and possibly some animals.[45][46] This enzyme transfers electrons directly from ubiquinol to oxygen.[47]

The electron transport pathways produced by these alternative NADH and ubiquinone oxidases have lower ATP yields than the full pathway. The advantages produced by a shortened pathway are not entirely clear. However, the alternative oxidase is produced in response to stresses such as cold, reactive oxygen species, and infection by pathogens, as well as other factors that inhibit the full electron transport chain.[48][49] Alternative pathways might, therefore, enhance an organism's resistance to injury, by reducing oxidative stress.[50]

Organization of complexes

[edit]The original model for how the respiratory chain complexes are organized was that they diffuse freely and independently in the mitochondrial membrane.[51] However, recent data suggest that the complexes might form higher-order structures called supercomplexes or "respirasomes".[52] In this model, the various complexes exist as organized sets of interacting enzymes.[53] These associations might allow channeling of substrates between the various enzyme complexes, increasing the rate and efficiency of electron transfer.[54] Within such mammalian supercomplexes, some components would be present in higher amounts than others, with some data suggesting a ratio between complexes I/II/III/IV and the ATP synthase of approximately 1:1:3:7:4.[55] However, the debate over this supercomplex hypothesis is not completely resolved, as some data do not appear to fit with this model.[19][56]

Prokaryotic electron transport chains

[edit]In contrast to the general similarity in structure and function of the electron transport chains in eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea possess a large variety of electron-transfer enzymes. These use an equally wide set of chemicals as substrates.[57] In common with eukaryotes, prokaryotic electron transport uses the energy released from the oxidation of a substrate to pump ions across a membrane and generate an electrochemical gradient. In the bacteria, oxidative phosphorylation in Escherichia coli is understood in most detail, while archaeal systems are at present poorly understood.[58]

The main difference between eukaryotic and prokaryotic oxidative phosphorylation is that bacteria and archaea use many different substances to donate or accept electrons. This allows prokaryotes to grow under a wide variety of environmental conditions.[59] In E. coli, for example, oxidative phosphorylation can be driven by a large number of pairs of reducing agents and oxidizing agents, which are listed below. The midpoint potential of a chemical measures how much energy is released when it is oxidized or reduced, with reducing agents having negative potentials and oxidizing agents positive potentials.

| Respiratory enzyme | Redox pair | Midpoint potential

(Volts) |

|---|---|---|

| Formate dehydrogenase | Bicarbonate / Formate | −0.43 |

| Hydrogenase | Proton / Hydrogen | −0.42 |

| NADH dehydrogenase | NAD+ / NADH | −0.32 |

| Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | DHAP / Gly-3-P | −0.19 |

| Pyruvate oxidase | Acetate + Carbon dioxide / Pyruvate | ? |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | Pyruvate / Lactate | −0.19 |

| D-amino acid dehydrogenase | 2-oxoacid + ammonia / D-amino acid | ? |

| Glucose dehydrogenase | Gluconate / Glucose | −0.14 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase | Fumarate / Succinate | +0.03 |

| Ubiquinol oxidase | Oxygen / Water | +0.82 |

| Nitrate reductase | Nitrate / Nitrite | +0.42 |

| Nitrite reductase | Nitrite / Ammonia | +0.36 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide reductase | DMSO / DMS | +0.16 |

| Trimethylamine N-oxide reductase | TMAO / TMA | +0.13 |

| Fumarate reductase | Fumarate / Succinate | +0.03 |

As shown above, E. coli can grow with reducing agents such as formate, hydrogen, or lactate as electron donors, and nitrate, DMSO, or oxygen as acceptors.[59] The larger the difference in midpoint potential between an oxidizing and reducing agent, the more energy is released when they react. Out of these compounds, the succinate/fumarate pair is unusual, as its midpoint potential is close to zero. Succinate can therefore be oxidized to fumarate if a strong oxidizing agent such as oxygen is available, or fumarate can be reduced to succinate using a strong reducing agent such as formate. These alternative reactions are catalyzed by succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate reductase, respectively.[61]

Some prokaryotes use redox pairs that have only a small difference in midpoint potential. For example, nitrifying bacteria such as Nitrobacter oxidize nitrite to nitrate, donating the electrons to oxygen. The small amount of energy released in this reaction is enough to pump protons and generate ATP, but not enough to produce NADH or NADPH directly for use in anabolism.[62] This problem is solved by using a nitrite oxidoreductase to produce enough proton-motive force to run part of the electron transport chain in reverse, causing complex I to generate NADH.[63][64]

Prokaryotes control their use of these electron donors and acceptors by varying which enzymes are produced, in response to environmental conditions.[65] This flexibility is possible because different oxidases and reductases use the same ubiquinone pool. This allows many combinations of enzymes to function together, linked by the common ubiquinol intermediate.[60] These respiratory chains therefore have a modular design, with easily interchangeable sets of enzyme systems.

In addition to this metabolic diversity, prokaryotes also possess a range of isozymes – different enzymes that catalyze the same reaction. For example, in E. coli, there are two different types of ubiquinol oxidase using oxygen as an electron acceptor. Under highly aerobic conditions, the cell uses an oxidase with a low affinity for oxygen that can transport two protons per electron. However, if levels of oxygen fall, they switch to an oxidase that transfers only one proton per electron, but has a high affinity for oxygen.[66]

ATP synthase (complex V)

[edit]ATP synthase, also called complex V, is the final enzyme in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. This enzyme is found in all forms of life and functions in the same way in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes.[67] The enzyme uses the energy stored in a proton gradient across a membrane to drive the synthesis of ATP from ADP and phosphate (Pi). Estimates of the number of protons required to synthesize one ATP have ranged from three to four,[68][69] with some suggesting cells can vary this ratio, to suit different conditions.[70]

| (6) |

This phosphorylation reaction is an equilibrium, which can be shifted by altering the proton-motive force. In the absence of a proton-motive force, the ATP synthase reaction will run from right to left, hydrolyzing ATP and pumping protons out of the matrix across the membrane. However, when the proton-motive force is high, the reaction is forced to run in the opposite direction; it proceeds from left to right, allowing protons to flow down their concentration gradient and turning ADP into ATP.[67] Indeed, in the closely related vacuolar type H+-ATPases, the hydrolysis reaction is used to acidify cellular compartments, by pumping protons and hydrolysing ATP.[71]

ATP synthase is a massive protein complex with a mushroom-like shape. The mammalian enzyme complex contains 16 subunits and has a mass of approximately 600 kilodaltons.[72] The portion embedded within the membrane is called FO and contains a ring of c subunits and the proton channel. The stalk and the ball-shaped headpiece is called F1 and is the site of ATP synthesis. The ball-shaped complex at the end of the F1 portion contains six proteins of two different kinds (three α subunits and three β subunits), whereas the "stalk" consists of one protein: the γ subunit, with the tip of the stalk extending into the ball of α and β subunits.[73] Both the α and β subunits bind nucleotides, but only the β subunits catalyze the ATP synthesis reaction. Reaching along the side of the F1 portion and back into the membrane is a long rod-like subunit that anchors the α and β subunits into the base of the enzyme.

As protons cross the membrane through the channel in the base of ATP synthase, the FO proton-driven motor rotates.[74] Rotation might be caused by changes in the ionization of amino acids in the ring of c subunits causing electrostatic interactions that propel the ring of c subunits past the proton channel.[75] This rotating ring in turn drives the rotation of the central axle (the γ subunit stalk) within the α and β subunits. The α and β subunits are prevented from rotating themselves by the side-arm, which acts as a stator. This movement of the tip of the γ subunit within the ball of α and β subunits provides the energy for the active sites in the β subunits to undergo a cycle of movements that produces and then releases ATP.[76]

This ATP synthesis reaction is called the binding change mechanism and involves the active site of a β subunit cycling between three states.[77] In the "open" state, ADP and phosphate enter the active site (shown in brown in the diagram). The protein then closes up around the molecules and binds them loosely – the "loose" state (shown in red). The enzyme then changes shape again and forces these molecules together, with the active site in the resulting "tight" state (shown in pink) binding the newly produced ATP molecule with very high affinity. Finally, the active site cycles back to the open state, releasing ATP and binding more ADP and phosphate, ready for the next cycle.

In some bacteria and archaea, ATP synthesis is driven by the movement of sodium ions through the cell membrane, rather than the movement of protons.[78][79] Archaea such as Methanococcus also contain the A1Ao synthase, a form of the enzyme that contains additional proteins with little similarity in sequence to other bacterial and eukaryotic ATP synthase subunits. It is possible that, in some species, the A1Ao form of the enzyme is a specialized sodium-driven ATP synthase,[80] but this might not be true in all cases.[79]

Oxidative phosphorylation - energetics

[edit]The transport of electrons from redox pair NAD+/ NADH to the final redox pair 1/2 O2/ H2O can be summarized as

1/2 O2 + NADH + H+ → H2O + NAD+

The potential difference between these two redox pairs is 1.14 volt, which is equivalent to -52 kcal/mol or -2600 kJ per 6 mol of O2.

When one NADH is oxidized through the electron transfer chain, three ATPs are produced, which is equivalent to 7.3 kcal/mol x 3 = 21.9 kcal/mol.

The conservation of the energy can be calculated by the following formula

Efficiency = (21.9 x 100%) / 52 = 42%

So we can conclude that when NADH is oxidized, about 42% of energy is conserved in the form of three ATPs and the remaining (58%) energy is lost as heat (unless the chemical energy of ATP under physiological conditions was underestimated).

Reactive oxygen species

[edit]Molecular oxygen is a good terminal electron acceptor because it is a strong oxidizing agent. The reduction of oxygen does involve potentially harmful intermediates.[81] Although the transfer of four electrons and four protons reduces oxygen to water, which is harmless, transfer of one or two electrons produces superoxide or peroxide anions, which are dangerously reactive.

| (7) |

These reactive oxygen species and their reaction products, such as the hydroxyl radical, are very harmful to cells, as they oxidize proteins and cause mutations in DNA. This cellular damage may contribute to disease and is proposed as one cause of aging.[82][83]

The cytochrome c oxidase complex is highly efficient at reducing oxygen to water, and it releases very few partly reduced intermediates; however small amounts of superoxide anion and peroxide are produced by the electron transport chain.[84] Particularly important is the reduction of coenzyme Q in complex III, as a highly reactive ubisemiquinone free radical is formed as an intermediate in the Q cycle. This unstable species can lead to electron "leakage" when electrons transfer directly to oxygen, forming superoxide.[85] As the production of reactive oxygen species by these proton-pumping complexes is greatest at high membrane potentials, it has been proposed that mitochondria regulate their activity to maintain the membrane potential within a narrow range that balances ATP production against oxidant generation.[86] For instance, oxidants can activate uncoupling proteins that reduce membrane potential.[87]

To counteract these reactive oxygen species, cells contain numerous antioxidant systems, including antioxidant vitamins such as vitamin C and vitamin E, and antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidases,[81] which detoxify the reactive species, limiting damage to the cell.

In hypoxic/anoxic conditions

[edit]As oxygen is fundamental for oxidative phosphorylation, a shortage in O2 level can alter ATP production rates. The proton motive force and ATP production can be maintained by intracellular acidosis.[88] Cytosolic protons that have accumulated with ATP hydrolysis and lactic acidosis can freely diffuse across the mitochondrial outer-membrane and acidify the inter-membrane space, hence directly contributing to the proton motive force and ATP production.

When exposed to hypoxia/anoxia (no oxygen), most animals will see damage done to their mitochondria.[89] From some species, these conditions can happen due to environmental variables, such as low tides,[90] low temperatures,[91] or general living conditions, like living in a hypoxic underground burrow.[92] In humans, these conditions are commonly met in medical emergencies such as strokes, ischemia, and asphyxia.

Despite this, or perhaps due to it, some species have developed their own defense mechanisms against anoxia/hypoxia, as well as during reperfusion/reoxygenation. These mechanisms are diverse and differ between endotherms and ectotherms and can differ even at the species level.

Endotherms

[edit]Hypoxia/anoxia intolerance

[edit]Most mammals and birds are intolerant to low/no oxygen conditions. For the heart, in the absence of oxygen, the first four complexes of the electron transport chain decrease in activity.[89] This will lead to protons leaking through the inner mitochondrial membrane without complexes I, III, and IV pushing protons back through to maintain the proton gradient. There is also electron leak (an event where electrons leak out of the electron transport chain), which happens because NADH dehydrogenase within Complex I becomes damaged, which allows for the production of ROS (reactive oxygen species) during ischemia.[93] This will lead to the reversing of Complex V, which forces protons from the matrix back into the inner membrane space, against their concentration gradient. Forcing protons against their concentration gradient requires energy, so Complex V uses up ATP as an energy source.[94]

Reoxygenation of intolerant animals

[edit]When oxygen re-enters the system, animals are faced with a different set of problems. Since ATP was used up during the anoxic period, it leads to a lack of ADP within the system.[95] This is due to ADP's natural degradation into AMP, resulting in ADP being drained from the system. With no ADP in the system, Complex V is unable to start, meaning the protons will not flow through it to enter the matrix.[95] Due to Complex V's reversal during anoxia, the proton gradient has become hyperpolarized (where the proton gradient is highly positively charged). Another factor in this problem is that succinate built up during anoxia, so when oxygen is reintroduced, succinate donates electrons to Complex II.[96][97] The hyperpolarized gradient and succinate buildup leads to reverse electron transport, causing oxidative stress,[98] which can lead to cellular damage and diseases.[99]

Hypoxia/anoxia tolerance

[edit]The naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) is a hypoxia-tolerant species that sleeps in deep burrows and in large colonies. The depth of these burrows reduces access to oxygen, and sleeping in large groups will deplete the area of oxygen quicker than usual, leading to hypoxia.[92] The naked mole rat has the unique ability to survive low oxygen conditions for no less than several hours, and zero oxygen conditions for 18 minutes.[100] One of the ways of combatting hypoxia in the brain is decreasing the reliance on oxygen for ATP production, achieved by decreased respiration rates and proton leak.[92]

Reoxygenation of tolerant animals

[edit]Hypoxia/anoxia tolerant species handle ROS production during reoxygenation better than the intolerant. In the cortex of the naked mole rats, they show better homeostasis of ROS production than intolerant species and seem to lack the burst of ROS that typically comes with reoxygenation.[100]

Ectotherms

[edit]Hypoxia/anoxia intolerance

[edit]Research on intolerant ectotherms is more limited than on tolerant ectotherms and intolerant endotherms, but it is shown that anoxia/hypoxia intolerance is different in terms for how long the intolerant survive as opposed to the tolerant between endotherms and ectotherms. While intolerant endotherms only last minutes, intolerant ectotherms can last hours, such as subtidal scallops (Argopecten irradians).[101] This difference in intolerance could be due to a couple of different factors. One advantage is that the ectothermic inner mitochondrial membrane is less leaky, so less protons will leak through the inner membrane due to differences in the phospholipid bilayer composition.[94] Another advantage ectotherms tend to have in this category is an ability for their mitochondria to properly function in a wide range of temperatures, such as the western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). While western fence lizards are not considered a hypoxia-tolerant animal, they still showed less temperature sensitivity in their mitochondria than mice mitochondria.[102]

Reoxygenation of intolerant animals

[edit]While it is unclear how reoxygenation affects intolerant ectotherms at the mitochondrial level, there is some research showing how some of them respond. In the hypoxia-sensitive shovelnose ray (Aptychotrema rostrata), it is shown that ROS production is lower upon reoxygenation compared to rays only exposed to normoxia (normal oxygen levels).[90] This differs from the hypoxia-sensitive endotherm, which would see an increase in ROS production. However, the ray's levels were still higher than the more hypoxia-tolerant Epaulette shark (Hemiscyllum ocellatum), which potentially sees hypoxia due to the bouts of low tides that can be seen in reef platforms.[90] Subtidal scallops will see both a decrease in maximal respiration and a depolarization of the membrane during reoxygenation.[101]

Hypoxia/anoxia tolerance

[edit]Hypoxia/Anoxia tolerant ectotherms have shown unique strategies for surviving anoxia. Pond turtles, such as the painted turtle (Chrysemys picta bellii), will experience anoxia during winter while they overwinter at the bottom of frozen ponds.[91] In their cardiac mitochondria, the reversing of Complex V,[103] the usage of ATP, and the build-up of succinate are all prevented during anoxia.[95] Crucian carps (Carassius carassius) also overwinter in frozen ponds and show no loss membrane potential in their cardiac mitochondria during anoxia, but this relies on complexes I and III to be active.[104]

Reoxygenation of tolerant animals

[edit]Pond turtles are able to completely avoid ROS production upon reoxygenation.[105] However, crucian carp cannot and are unable to prevent the death of brain cells upon reoxygenation.[106]

Inhibitors

[edit]There are several well-known drugs and toxins that inhibit oxidative phosphorylation. Although any one of these toxins inhibits only one enzyme in the electron transport chain, inhibition of any step in this process will halt the rest of the process. For example, if oligomycin inhibits ATP synthase, protons cannot pass back into the mitochondrion.[107] As a result, the proton pumps are unable to operate, as the gradient becomes too strong for them to overcome. NADH is then no longer oxidized and the citric acid cycle ceases to operate because the concentration of NAD+ falls below the concentration that these enzymes can use.

Many site-specific inhibitors of the electron transport chain have contributed to the present knowledge of mitochondrial respiration. Synthesis of ATP is also dependent on the electron transport chain, so all site-specific inhibitors also inhibit ATP formation. The fish poison rotenone, the barbiturate drug amytal, and the antibiotic piericidin A inhibit NADH and coenzyme Q.[108]

Carbon monoxide, cyanide, hydrogen sulphide and azide effectively inhibit cytochrome oxidase. Carbon monoxide reacts with the reduced form of the cytochrome while cyanide and azide react with the oxidised form. An antibiotic, antimycin A, and British anti-Lewisite, an antidote used against chemical weapons, are the two important inhibitors of the site between cytochrome B and C1.[108]

| Compounds | Use | Site of action | Effect on oxidative phosphorylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanide Carbon monoxide Azide Hydrogen sulfide |

Poisons | Complex IV | Inhibit the electron transport chain by binding more strongly than oxygen to the Fe–Cu center in cytochrome c oxidase, preventing the reduction of oxygen.[109] |

| Oligomycin | Antibiotic | Complex V | Inhibits ATP synthase by blocking the flow of protons through the Fo subunit.[107] |

| CCCP 2,4-Dinitrophenol |

Poisons, weight-loss[N 1] | Inner membrane | Ionophores that disrupt the proton gradient by carrying protons across a membrane. This ionophore uncouples proton pumping from ATP synthesis because it carries protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane.[110] |

| Rotenone | Pesticide | Complex I | Prevents the transfer of electrons from complex I to ubiquinone by blocking the ubiquinone-binding site.[111] |

| Malonate and oxaloacetate | Poisons | Complex II | Competitive inhibitors of succinate dehydrogenase (complex II).[112] |

| Antimycin A | Piscicide | Complex III | Binds to the Qi site of cytochrome c reductase, thereby inhibiting the oxidation of ubiquinol. |

Not all inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation are toxins. In brown adipose tissue, regulated proton channels called uncoupling proteins can uncouple respiration from ATP synthesis.[113] This rapid respiration produces heat, and is particularly important as a way of maintaining body temperature for hibernating animals, although these proteins may also have a more general function in cells' responses to stress.[114]

History

[edit]The field of oxidative phosphorylation began with the report in 1906 by Arthur Harden of a vital role for phosphate in cellular fermentation, but initially only sugar phosphates were known to be involved.[115] However, in the early 1940s, the link between the oxidation of sugars and the generation of ATP was firmly established by Herman Kalckar,[116] confirming the central role of ATP in energy transfer that had been proposed by Fritz Albert Lipmann in 1941.[117] Later, in 1949, Morris Friedkin and Albert L. Lehninger proved that the coenzyme NADH linked metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle and the synthesis of ATP.[118] The term oxidative phosphorylation was coined by Volodymyr Belitser in 1939.[119][120]

For another twenty years, the mechanism by which ATP is generated remained mysterious, with scientists searching for an elusive "high-energy intermediate" that would link oxidation and phosphorylation reactions.[121] This puzzle was solved by Peter D. Mitchell with the publication of the chemiosmotic theory in 1961.[122] At first, this proposal was highly controversial, but it was slowly accepted and Mitchell was awarded a Nobel prize in 1978.[123][124] Subsequent research concentrated on purifying and characterizing the enzymes involved, with major contributions being made by David E. Green on the complexes of the electron-transport chain, as well as Efraim Racker on the ATP synthase.[125] A critical step towards solving the mechanism of the ATP synthase was provided by Paul D. Boyer, by his development in 1973 of the "binding change" mechanism, followed by his radical proposal of rotational catalysis in 1982.[77][126] More recent work has included structural studies on the enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation by John E. Walker, with Walker and Boyer being awarded a Nobel Prize in 1997.[127]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ DNP was extensively used as an anti-obesity medication in the 1930s but was ultimately discontinued due to its dangerous side effects. However, illicit use of the drug for this purpose continues today. See 2,4-Dinitrophenol#Dieting aid[broken anchor] for more information.

References

[edit]- ^ "oxidative Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ Voet, D.; Voet, J. G. (2004). "Biochemistry", 3rd ed., p. 804, Wiley.ISBN 0-471-19350-X.

- ^ Mitchell P, Moyle J (January 1967). "Chemiosmotic hypothesis of oxidative phosphorylation". Nature. 213 (5072): 137–139. Bibcode:1967Natur.213..137M. doi:10.1038/213137a0. PMID 4291593. S2CID 4149605.

- ^ a b Dimroth P, Kaim G, Matthey U (January 2000). "Crucial role of the membrane potential for ATP synthesis by F(1)F(o) ATP synthases". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (Pt 1): 51–59. Bibcode:2000JExpB.203...51D. doi:10.1242/jeb.203.1.51. PMID 10600673. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d Schultz BE, Chan SI (2001). "Structures and proton-pumping strategies of mitochondrial respiratory enzymes". Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 30: 23–65. doi:10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.23. PMID 11340051.

- ^ Rich PR (December 2003). "The molecular machinery of Keilin's respiratory chain". Biochemical Society Transactions. 31 (Pt 6): 1095–1105. doi:10.1042/bst0311095. PMID 14641005.

- ^ Porter RK, Brand MD (September 1995). "Mitochondrial proton conductance and H+/O ratio are independent of electron transport rate in isolated hepatocytes". The Biochemical Journal. 310 (Pt 2): 379–382. doi:10.1042/bj3100379. PMC 1135905. PMID 7654171.

- ^ Mathews FS (1985). "The structure, function and evolution of cytochromes". Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 45 (1): 1–56. doi:10.1016/0079-6107(85)90004-5. PMID 3881803.

- ^ Wood PM (December 1983). "Why do c-type cytochromes exist?". FEBS Letters. 164 (2): 223–226. Bibcode:1983FEBSL.164..223W. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(83)80289-0. PMID 6317447. S2CID 7685958.

- ^ Crane FL (December 2001). "Biochemical functions of coenzyme Q10". Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 20 (6): 591–598. doi:10.1080/07315724.2001.10719063. PMID 11771674. S2CID 28013583.

- ^ Mitchell P (December 1979). "Keilin's respiratory chain concept and its chemiosmotic consequences". Science. 206 (4423): 1148–1159. Bibcode:1979Sci...206.1148M. doi:10.1126/science.388618. PMID 388618.

- ^ Søballe B, Poole RK (August 1999). "Microbial ubiquinones: multiple roles in respiration, gene regulation and oxidative stress management" (PDF). Microbiology. 145 (8): 1817–1830. doi:10.1099/13500872-145-8-1817. PMID 10463148. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-05-29.

- ^ Johnson DC, Dean DR, Smith AD, Johnson MK (2005). "Structure, function, and formation of biological iron-sulfur clusters". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 74: 247–281. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133518. PMID 15952888.

- ^ Page CC, Moser CC, Chen X, Dutton PL (November 1999). "Natural engineering principles of electron tunnelling in biological oxidation-reduction". Nature. 402 (6757): 47–52. Bibcode:1999Natur.402...47P. doi:10.1038/46972. PMID 10573417. S2CID 4431405.

- ^ Leys D, Scrutton NS (December 2004). "Electrical circuitry in biology: emerging principles from protein structure". Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 14 (6): 642–647. doi:10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.002. PMID 15582386.

- ^ Boxma B, de Graaf RM, van der Staay GW, van Alen TA, Ricard G, Gabaldón T, et al. (March 2005). "An anaerobic mitochondrion that produces hydrogen". Nature. 434 (7029): 74–79. Bibcode:2005Natur.434...74B. doi:10.1038/nature03343. PMID 15744302. S2CID 4401178.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Medical CHEMISTRY Compendium. By Anders Overgaard Pedersen and Henning Nielsen. Aarhus University. 2008

- ^ a b Hirst J (June 2005). "Energy transduction by respiratory complex I--an evaluation of current knowledge". Biochemical Society Transactions. 33 (Pt 3): 525–529. doi:10.1042/BST0330525. PMID 15916556.

- ^ a b Lenaz G, Fato R, Genova ML, Bergamini C, Bianchi C, Biondi A (2006). "Mitochondrial Complex I: structural and functional aspects". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1757 (9–10): 1406–1420. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.007. PMID 16828051.

- ^ a b Sazanov LA, Hinchliffe P (March 2006). "Structure of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory complex I from Thermus thermophilus". Science. 311 (5766): 1430–1436. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1430S. doi:10.1126/science.1123809. PMID 16469879. S2CID 1892332.

- ^ Efremov RG, Baradaran R, Sazanov LA (May 2010). "The architecture of respiratory complex I". Nature. 465 (7297): 441–445. Bibcode:2010Natur.465..441E. doi:10.1038/nature09066. PMID 20505720. S2CID 4372778.

- ^ Baranova EA, Holt PJ, Sazanov LA (February 2007). "Projection structure of the membrane domain of Escherichia coli respiratory complex I at 8 A resolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 366 (1): 140–154. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.026. PMID 17157874.

- ^ Friedrich T, Böttcher B (January 2004). "The gross structure of the respiratory complex I: a Lego System". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1608 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.10.002. PMID 14741580.

- ^ Hirst J (December 2009). "Towards the molecular mechanism of respiratory complex I". The Biochemical Journal. 425 (2): 327–339. doi:10.1042/BJ20091382. PMID 20025615.

- ^ Cecchini G (2003). "Function and structure of complex II of the respiratory chain". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 72: 77–109. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161700. PMID 14527321.

- ^ Yankovskaya V, Horsefield R, Törnroth S, Luna-Chavez C, Miyoshi H, Léger C, et al. (January 2003). "Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation". Science. 299 (5607): 700–704. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..700Y. doi:10.1126/science.1079605. PMID 12560550. S2CID 29222766.

- ^ Horsefield R, Iwata S, Byrne B (April 2004). "Complex II from a structural perspective". Current Protein & Peptide Science. 5 (2): 107–118. doi:10.2174/1389203043486847. PMID 15078221.

- ^ Kita K, Hirawake H, Miyadera H, Amino H, Takeo S (January 2002). "Role of complex II in anaerobic respiration of the parasite mitochondria from Ascaris suum and Plasmodium falciparum". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1553 (1–2): 123–139. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(01)00237-7. PMID 11803022.

- ^ Painter HJ, Morrisey JM, Mather MW, Vaidya AB (March 2007). "Specific role of mitochondrial electron transport in blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum". Nature. 446 (7131): 88–91. Bibcode:2007Natur.446...88P. doi:10.1038/nature05572. PMID 17330044. S2CID 4421676.

- ^ Ramsay RR, Steenkamp DJ, Husain M (February 1987). "Reactions of electron-transfer flavoprotein and electron-transfer flavoprotein: ubiquinone oxidoreductase". The Biochemical Journal. 241 (3): 883–892. doi:10.1042/bj2410883. PMC 1147643. PMID 3593226.

- ^ Zhang J, Frerman FE, Kim JJ (October 2006). "Structure of electron transfer flavoprotein-ubiquinone oxidoreductase and electron transfer to the mitochondrial ubiquinone pool". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 103 (44): 16212–16217. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10316212Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0604567103. PMC 1637562. PMID 17050691.

- ^ Ikeda Y, Dabrowski C, Tanaka K (January 1983). "Separation and properties of five distinct acyl-CoA dehydrogenases from rat liver mitochondria. Identification of a new 2-methyl branched chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 258 (2): 1066–1076. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)33160-0. PMID 6401712. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ Ruzicka FJ, Beinert H (December 1977). "A new iron-sulfur flavoprotein of the respiratory chain. A component of the fatty acid beta oxidation pathway" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 252 (23): 8440–8445. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)75238-7. PMID 925004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ Ishizaki K, Larson TR, Schauer N, Fernie AR, Graham IA, Leaver CJ (September 2005). "The critical role of Arabidopsis electron-transfer flavoprotein:ubiquinone oxidoreductase during dark-induced starvation". The Plant Cell. 17 (9): 2587–2600. Bibcode:2005PlanC..17.2587I. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.035162. PMC 1197437. PMID 16055629.

- ^ Berry EA, Guergova-Kuras M, Huang LS, Crofts AR (2000). "Structure and function of cytochrome bc complexes" (PDF). Annual Review of Biochemistry. 69: 1005–1075. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.319.5709. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.1005. PMID 10966481. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-28.

- ^ Crofts AR (2004). "The cytochrome bc1 complex: function in the context of structure". Annual Review of Physiology. 66: 689–733. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.150251. PMID 14977419.

- ^ Iwata S, Lee JW, Okada K, Lee JK, Iwata M, Rasmussen B, et al. (July 1998). "Complete structure of the 11-subunit bovine mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex". Science. 281 (5373): 64–71. Bibcode:1998Sci...281...64I. doi:10.1126/science.281.5373.64. PMID 9651245.

- ^ Trumpower BL (July 1990). "The protonmotive Q cycle. Energy transduction by coupling of proton translocation to electron transfer by the cytochrome bc1 complex" (PDF). The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (20): 11409–11412. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)38410-8. PMID 2164001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ Hunte C, Palsdottir H, Trumpower BL (June 2003). "Protonmotive pathways and mechanisms in the cytochrome bc1 complex". FEBS Letters. 545 (1): 39–46. Bibcode:2003FEBSL.545...39H. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00391-0. PMID 12788490. S2CID 13942619.

- ^ Calhoun MW, Thomas JW, Gennis RB (August 1994). "The cytochrome oxidase superfamily of redox-driven proton pumps". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 19 (8): 325–330. doi:10.1016/0968-0004(94)90071-X. PMID 7940677.

- ^ Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, et al. (May 1996). "The whole structure of the 13-subunit oxidized cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 A". Science. 272 (5265): 1136–1144. Bibcode:1996Sci...272.1136T. doi:10.1126/science.272.5265.1136. PMID 8638158. S2CID 20860573.

- ^ Yoshikawa S, Muramoto K, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Aoyama H, Tsukihara T, Shimokata K, et al. (2006). "Proton pumping mechanism of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1757 (9–10): 1110–1116. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.06.004. PMID 16904626.

- ^ Rasmusson AG, Soole KL, Elthon TE (2004). "Alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases of plant mitochondria". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 55: 23–39. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141720. PMID 15725055.

- ^ Menz RI, Day DA (September 1996). "Purification and characterization of a 43-kDa rotenone-insensitive NADH dehydrogenase from plant mitochondria". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (38): 23117–23120. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.38.23117. PMID 8798503. S2CID 893754.

- ^ McDonald A, Vanlerberghe G (June 2004). "Branched mitochondrial electron transport in the Animalia: presence of alternative oxidase in several animal phyla". IUBMB Life. 56 (6): 333–341. doi:10.1080/1521-6540400000876. PMID 15370881.

- ^ Sluse FE, Jarmuszkiewicz W (June 1998). "Alternative oxidase in the branched mitochondrial respiratory network: an overview on structure, function, regulation, and role". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research = Revista Brasileira de Pesquisas Medicas e Biologicas. 31 (6): 733–747. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X1998000600003. PMID 9698817.

- ^ Moore AL, Siedow JN (August 1991). "The regulation and nature of the cyanide-resistant alternative oxidase of plant mitochondria". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1059 (2): 121–140. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(05)80197-5. PMID 1883834.

- ^ Vanlerberghe GC, McIntosh L (June 1997). "ALTERNATIVE OXIDASE: From Gene to Function". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 48: 703–734. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.703. PMID 15012279.

- ^ Ito Y, Saisho D, Nakazono M, Tsutsumi N, Hirai A (December 1997). "Transcript levels of tandem-arranged alternative oxidase genes in rice are increased by low temperature". Gene. 203 (2): 121–129. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00502-7. PMID 9426242.

- ^ Maxwell DP, Wang Y, McIntosh L (July 1999). "The alternative oxidase lowers mitochondrial reactive oxygen production in plant cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (14): 8271–8276. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.8271M. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.14.8271. PMC 22224. PMID 10393984.

- ^ Lenaz G (December 2001). "A critical appraisal of the mitochondrial coenzyme Q pool". FEBS Letters. 509 (2): 151–155. Bibcode:2001FEBSL.509..151L. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03172-6. PMID 11741580. S2CID 46138989.

- ^ Heinemeyer J, Braun HP, Boekema EJ, Kouril R (April 2007). "A structural model of the cytochrome C reductase/oxidase supercomplex from yeast mitochondria". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (16): 12240–12248. doi:10.1074/jbc.M610545200. PMID 17322303. S2CID 18123642.

- ^ Schägger H, Pfeiffer K (April 2000). "Supercomplexes in the respiratory chains of yeast and mammalian mitochondria". The EMBO Journal. 19 (8): 1777–1783. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.8.1777. PMC 302020. PMID 10775262.

- ^ Schägger H (September 2002). "Respiratory chain supercomplexes of mitochondria and bacteria". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1555 (1–3): 154–159. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(02)00271-2. PMID 12206908.

- ^ Schägger H, Pfeiffer K (October 2001). "The ratio of oxidative phosphorylation complexes I-V in bovine heart mitochondria and the composition of respiratory chain supercomplexes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (41): 37861–37867. doi:10.1074/jbc.M106474200. PMID 11483615. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29.

- ^ Gupte S, Wu ES, Hoechli L, Hoechli M, Jacobson K, Sowers AE, et al. (May 1984). "Relationship between lateral diffusion, collision frequency, and electron transfer of mitochondrial inner membrane oxidation-reduction components". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 81 (9): 2606–2610. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81.2606G. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.9.2606. PMC 345118. PMID 6326133.

- ^ Nealson KH (January 1999). "Post-Viking microbiology: new approaches, new data, new insights". Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere. 29 (1): 73–93. Bibcode:1999OLEB...29...73N. doi:10.1023/A:1006515817767. PMID 11536899. S2CID 12289639.

- ^ Schäfer G, Engelhard M, Müller V (September 1999). "Bioenergetics of the Archaea". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 63 (3): 570–620. doi:10.1128/MMBR.63.3.570-620.1999. PMC 103747. PMID 10477309.

- ^ a b Ingledew WJ, Poole RK (September 1984). "The respiratory chains of Escherichia coli". Microbiological Reviews. 48 (3): 222–271. doi:10.1128/mmbr.48.3.222-271.1984. PMC 373010. PMID 6387427.

- ^ a b Unden G, Bongaerts J (July 1997). "Alternative respiratory pathways of Escherichia coli: energetics and transcriptional regulation in response to electron acceptors". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1320 (3): 217–234. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(97)00034-0. PMID 9230919.

- ^ Cecchini G, Schröder I, Gunsalus RP, Maklashina E (January 2002). "Succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate reductase from Escherichia coli". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1553 (1–2): 140–157. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(01)00238-9. PMID 11803023.

- ^ Freitag A, Bock E (1990). "Energy conservation in Nitrobacter". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 66 (1–3): 157–62. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb03989.x.

- ^ Starkenburg SR, Chain PS, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Hauser L, Land ML, Larimer FW, et al. (March 2006). "Genome sequence of the chemolithoautotrophic nitrite-oxidizing bacterium Nitrobacter winogradskyi Nb-255". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (3): 2050–2063. Bibcode:2006ApEnM..72.2050S. doi:10.1128/AEM.72.3.2050-2063.2006. PMC 1393235. PMID 16517654.

- ^ Yamanaka T, Fukumori Y (December 1988). "The nitrite oxidizing system of Nitrobacter winogradskyi". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 54 (4): 259–270. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02746.x. PMID 2856189.

- ^ Iuchi S, Lin EC (July 1993). "Adaptation of Escherichia coli to redox environments by gene expression". Molecular Microbiology. 9 (1): 9–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01664.x. PMID 8412675. S2CID 39165641.

- ^ Calhoun MW, Oden KL, Gennis RB, de Mattos MJ, Neijssel OM (May 1993). "Energetic efficiency of Escherichia coli: effects of mutations in components of the aerobic respiratory chain" (PDF). Journal of Bacteriology. 175 (10): 3020–3025. doi:10.1128/jb.175.10.3020-3025.1993. PMC 204621. PMID 8491720. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-27.

- ^ a b Boyer PD (1997). "The ATP synthase--a splendid molecular machine". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 66: 717–749. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.717. PMID 9242922.

- ^ Van Walraven HS, Strotmann H, Schwarz O, Rumberg B (February 1996). "The H+/ATP coupling ratio of the ATP synthase from thiol-modulated chloroplasts and two cyanobacterial strains is four". FEBS Letters. 379 (3): 309–313. Bibcode:1996FEBSL.379..309V. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(95)01536-1. PMID 8603713. S2CID 35989618.

- ^ Yoshida M, Muneyuki E, Hisabori T (September 2001). "ATP synthase--a marvellous rotary engine of the cell". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 2 (9): 669–677. doi:10.1038/35089509. PMID 11533724. S2CID 3926411.

- ^ Schemidt RA, Qu J, Williams JR, Brusilow WS (June 1998). "Effects of carbon source on expression of F0 genes and on the stoichiometry of the c subunit in the F1F0 ATPase of Escherichia coli". Journal of Bacteriology. 180 (12): 3205–3208. doi:10.1128/jb.180.12.3205-3208.1998. PMC 107823. PMID 9620972.

- ^ Nelson N, Perzov N, Cohen A, Hagai K, Padler V, Nelson H (January 2000). "The cellular biology of proton-motive force generation by V-ATPases". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (Pt 1): 89–95. Bibcode:2000JExpB.203...89N. doi:10.1242/jeb.203.1.89. PMID 10600677. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ Rubinstein JL, Walker JE, Henderson R (December 2003). "Structure of the mitochondrial ATP synthase by electron cryomicroscopy". The EMBO Journal. 22 (23): 6182–6192. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg608. PMC 291849. PMID 14633978.

- ^ Leslie AG, Walker JE (April 2000). "Structural model of F1-ATPase and the implications for rotary catalysis". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 355 (1396): 465–471. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0588. PMC 1692760. PMID 10836500.

- ^ Noji H, Yoshida M (January 2001). "The rotary machine in the cell, ATP synthase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (3): 1665–1668. doi:10.1074/jbc.R000021200. PMID 11080505. S2CID 30953216.

- ^ Capaldi RA, Aggeler R (March 2002). "Mechanism of the F(1)F(0)-type ATP synthase, a biological rotary motor". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 27 (3): 154–160. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(01)02051-5. PMID 11893513.

- ^ Dimroth P, von Ballmoos C, Meier T (March 2006). "Catalytic and mechanical cycles in F-ATP synthases. Fourth in the Cycles Review Series". EMBO Reports. 7 (3): 276–282. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400646. PMC 1456893. PMID 16607397.

- ^ a b Gresser MJ, Myers JA, Boyer PD (October 1982). "Catalytic site cooperativity of beef heart mitochondrial F1 adenosine triphosphatase. Correlations of initial velocity, bound intermediate, and oxygen exchange measurements with an alternating three-site model". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 257 (20): 12030–12038. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)33672-X. PMID 6214554. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ Dimroth P (1994). "Bacterial sodium ion-coupled energetics". Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 65 (4): 381–395. doi:10.1007/BF00872221. PMID 7832594. S2CID 23763996.

- ^ a b Becher B, Müller V (May 1994). "Delta mu Na+ drives the synthesis of ATP via an delta mu Na(+)-translocating F1F0-ATP synthase in membrane vesicles of the archaeon Methanosarcina mazei Gö1". Journal of Bacteriology. 176 (9): 2543–2550. doi:10.1128/jb.176.9.2543-2550.1994. PMC 205391. PMID 8169202.

- ^ Müller V (February 2004). "An exceptional variability in the motor of archael A1A0 ATPases: from multimeric to monomeric rotors comprising 6-13 ion binding sites". Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 36 (1): 115–125. doi:10.1023/B:JOBB.0000019603.68282.04. PMID 15168615. S2CID 24887884.

- ^ a b Davies KJ (1995). "Oxidative stress: the paradox of aerobic life". Biochemical Society Symposium. 61: 1–31. doi:10.1042/bss0610001. PMID 8660387.

- ^ Rattan SI (December 2006). "Theories of biological aging: genes, proteins, and free radicals" (PDF). Free Radical Research. 40 (12): 1230–1238. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.476.9259. doi:10.1080/10715760600911303. PMID 17090411. S2CID 11125090. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-06-14. Retrieved 2017-10-27.

- ^ Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J (2007). "Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease". The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 39 (1): 44–84. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. PMID 16978905.

- ^ Raha S, Robinson BH (October 2000). "Mitochondria, oxygen free radicals, disease and ageing". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 25 (10): 502–508. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(00)01674-1. PMID 11050436.

- ^ Finkel T, Holbrook NJ (November 2000). "Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing". Nature. 408 (6809): 239–247. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..239F. doi:10.1038/35041687. PMID 11089981. S2CID 2502238.

- ^ Kadenbach B, Ramzan R, Wen L, Vogt S (March 2010). "New extension of the Mitchell Theory for oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria of living organisms". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1800 (3): 205–212. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.04.019. PMID 19409964.

- ^ Echtay KS, Roussel D, St-Pierre J, Jekabsons MB, Cadenas S, Stuart JA, et al. (January 2002). "Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins". Nature. 415 (6867): 96–99. Bibcode:2002Natur.415...96E. doi:10.1038/415096a. PMID 11780125. S2CID 4349744.

- ^ Devaux JB, Hedges CP, Birch N, Herbert N, Renshaw GM, Hickey AJ (January 2019). "Acidosis Maintains the Function of Brain Mitochondria in Hypoxia-Tolerant Triplefin Fish: A Strategy to Survive Acute Hypoxic Exposure?". Frontiers in Physiology. 9: 1941. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01941. PMC 6346031. PMID 30713504.

- ^ a b Lesnefsky EJ, Chen Q, Tandler B, Hoppel CL (January 2017). "Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion: Implications for Novel Therapies". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 57: 535–565. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010715-103335. PMC 11060135. PMID 27860548.

- ^ a b c Hickey AJ, Renshaw GM, Speers-Roesch B, Richards JG, Wang Y, Farrell AP, et al. (January 2012). "A radical approach to beating hypoxia: depressed free radical release from heart fibres of the hypoxia-tolerant epaulette shark (Hemiscyllum ocellatum)". Journal of Comparative Physiology. B, Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 182 (1): 91–100. doi:10.1007/s00360-011-0599-6. PMID 21748398.

- ^ a b Hawrysh PJ, Myrka AM, Buck LT (2022). "Review: A history and perspective of mitochondria in the context of anoxia tolerance". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 260: 110733. doi:10.1016/j.cbpb.2022.110733. PMID 35288242.

- ^ a b c Pamenter ME, Lau GY, Richards JG, Milsom WK (February 2018). "Naked mole rat brain mitochondria electron transport system flux and H+ leak are reduced during acute hypoxia". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 221 (Pt 4): jeb171397. doi:10.1242/jeb.171397. PMID 29361591.

- ^ Chen Q, Camara AK, Stowe DF, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ (January 2007). "Modulation of electron transport protects cardiac mitochondria and decreases myocardial injury during ischemia and reperfusion". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 292 (1): C137–C147. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00270.2006. PMID 16971498.

- ^ a b St-Pierre J, Brand MD, Boutilier RG (July 2000). "Mitochondria as ATP consumers: cellular treason in anoxia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 97 (15): 8670–8674. Bibcode:2000PNAS...97.8670S. doi:10.1073/pnas.140093597. PMC 27006. PMID 10890886.

- ^ a b c Bundgaard A, James AM, Gruszczyk AV, Martin J, Murphy MP, Fago A (February 2019). "Metabolic adaptations during extreme anoxia in the turtle heart and their implications for ischemia-reperfusion injury". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 2850. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.2850B. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39836-5. PMC 6391391. PMID 30808950.

- ^ Bundgaard A, Borowiec BG, Lau GY (March 2024). "Are reactive oxygen species always bad? Lessons from hypoxic ectotherms". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 227 (6): jeb246549. Bibcode:2024JExpB.227B6549B. doi:10.1242/jeb.246549. PMID 38533673.

- ^ Chouchani ET, Pell VR, Gaude E, Aksentijević D, Sundier SY, Robb EL, et al. (November 2014). "Ischaemic accumulation of succinate controls reperfusion injury through mitochondrial ROS". Nature. 515 (7527): 431–435. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..431C. doi:10.1038/nature13909. PMC 4255242. PMID 25383517.

- ^ Murphy MP (January 2009). "How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species". The Biochemical Journal. 417 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1042/BJ20081386. PMC 2605959. PMID 19061483.

- ^ Bolisetty S, Jaimes EA (March 2013). "Mitochondria and reactive oxygen species: physiology and pathophysiology". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 14 (3): 6306–6344. doi:10.3390/ijms14036306. PMC 3634422. PMID 23528859.

- ^ a b Eaton L, Wang T, Roy M, Pamenter ME (2023). "Naked Mole-Rat Cortex Maintains Reactive Oxygen Species Homeostasis During In Vitro Hypoxia or Ischemia and Reperfusion". Current Neuropharmacology. 21 (6): 1450–1461. doi:10.2174/1570159X20666220327220929. PMC 10324332. PMID 35339183.

- ^ a b Ivanina AV, Nesmelova I, Leamy L, Sokolov EP, Sokolova IM (June 2016). "Intermittent hypoxia leads to functional reorganization of mitochondria and affects cellular bioenergetics in marine molluscs". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 219 (Pt 11): 1659–1674. Bibcode:2016JExpB.219.1659I. doi:10.1242/jeb.134700. PMID 27252455.

- ^ Berner NJ (September 1999). "Oxygen consumption by mitochondria from an endotherm and an ectotherm". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part B, Biochemistry & Molecular Biology. 124 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1016/S0305-0491(99)00093-0. PMID 10582317.

- ^ Galli GL, Lau GY, Richards JG (September 2013). "Beating oxygen: chronic anoxia exposure reduces mitochondrial F1FO-ATPase activity in turtle (Trachemys scripta) heart". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 216 (Pt 17): 3283–3293. Bibcode:2013JExpB.216.3283G. doi:10.1242/jeb.087155. PMC 4074260. PMID 23926310.

- ^ Scott MA, Fagernes CE, Nilsson GE, Stensløkken KO (October 2024). "Maintained mitochondrial integrity without oxygen in the anoxia-tolerant crucian carp". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 227 (20): jeb247409. Bibcode:2024JExpB.227B7409S. doi:10.1242/jeb.247409. PMC 11418198. PMID 38779846.

- ^ Bundgaard A, Gruszczyk AV, Prag HA, Williams C, McIntyre A, Ruhr IM, et al. (May 2023). "Low production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species after anoxia and reoxygenation in turtle hearts". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 226 (9): jeb245516. Bibcode:2023JExpB.226B5516B. doi:10.1242/jeb.245516. PMC 10184768. PMID 37066839.

- ^ Bundgaard A, Ruhr IM, Fago A, Galli GL (April 2020). "Metabolic adaptations to anoxia and reoxygenation: New lessons from freshwater turtles and crucian carp". Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research. 11: 55–64. doi:10.1016/j.coemr.2020.01.002.

- ^ a b Joshi S, Huang YG (August 1991). "ATP synthase complex from bovine heart mitochondria: the oligomycin sensitivity conferring protein is essential for dicyclohexyl carbodiimide-sensitive ATPase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1067 (2): 255–258. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(91)90051-9. PMID 1831660.

- ^ a b Satyanarayana U (2002). Biochemistry (2nd ed.). Kolkata, India: Books and Allied. ISBN 8187134801. OCLC 71209231.

- ^ Tsubaki M (January 1993). "Fourier-transform infrared study of cyanide binding to the Fea3-CuB binuclear site of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase: implication of the redox-linked conformational change at the binuclear site". Biochemistry. 32 (1): 164–173. doi:10.1021/bi00052a022. PMID 8380331.

- ^ Heytler PG (1979). "Uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation". In Sidney Fleischer, Lester Packer (eds.). Biomembranes Part F: Bioenergetics: Oxidative Phosphorylation. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 55. pp. 462–472. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(79)55060-5. ISBN 978-0-12-181955-2. PMID 156853.

- ^ Lambert AJ, Brand MD (September 2004). "Inhibitors of the quinone-binding site allow rapid superoxide production from mitochondrial NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I)". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (38): 39414–39420. doi:10.1074/jbc.M406576200. PMID 15262965. S2CID 26620903.

- ^ Dervartanian DV, Veeger C (November 1964). "Studies on Succinate Dehydrogenase. I. Spectral Properties of the Purified Enzyme and Formation of Enzyme-Competitive Inhibitor Complexes". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Specialized Section on Enzymological Subjects. 92 (2): 233–247. doi:10.1016/0926-6569(64)90182-8. PMID 14249115.

- ^ Ricquier D, Bouillaud F (January 2000). "The uncoupling protein homologues: UCP1, UCP2, UCP3, StUCP and AtUCP". The Biochemical Journal. 345 (Pt 2): 161–179. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3450161. PMC 1220743. PMID 10620491.

- ^ Borecký J, Vercesi AE (2005). "Plant uncoupling mitochondrial protein and alternative oxidase: energy metabolism and stress". Bioscience Reports. 25 (3–4): 271–286. doi:10.1007/s10540-005-2889-2. PMID 16283557. S2CID 18598358.

- ^ Harden A, Young WJ (1906). "The alcoholic ferment of yeast-juice". Proceedings of the Royal Society. B (77): 405–20. doi:10.1098/rspb.1906.0029.

- ^ Kalckar HM (November 1974). "Origins of the concept oxidative phosphorylation". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 5 (1–2): 55–63. doi:10.1007/BF01874172. PMID 4279328. S2CID 26999163.

- ^ Lipmann F (1941). "Metabolic generation and utilization of phosphate bond energy". Adv Enzymol. 1: 99–162. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674366701.c141. ISBN 9780674366701.

- ^ Friedkin M, Lehninger AL (April 1949). "Esterification of inorganic phosphate coupled to electron transport between dihydrodiphosphopyridine nucleotide and oxygen". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 178 (2): 611–644. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)56879-4. PMID 18116985. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008.

- ^ Kalckar HM (1991). "50 years of biological research--from oxidative phosphorylation to energy requiring transport regulation". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 60: 1–37. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.60.070191.000245. PMID 1883194.

- ^ Belitser VA, Tsibakova ET (1939). "About phosphorilation mechanism coupled with respiration". Biokhimiya. 4: 516–534.

- ^ Slater EC (November 1953). "Mechanism of phosphorylation in the respiratory chain". Nature. 172 (4387): 975–978. Bibcode:1953Natur.172..975S. doi:10.1038/172975a0. PMID 13111237. S2CID 4153659.

- ^ Mitchell P (July 1961). "Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism". Nature. 191 (4784): 144–148. Bibcode:1961Natur.191..144M. doi:10.1038/191144a0. PMID 13771349. S2CID 1784050.

- ^ Saier Jr MH. Peter Mitchell and the Vital Force. OCLC 55202414.

- ^ Mitchell P (1978). "David Keilin's Respiratory Chain Concept and Its Chemiosmotic Consequences" (PDF). Nobel lecture. Nobel Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ Pullman ME, Penefsky HS, Datta A, Racker E (November 1960). "Partial resolution of the enzymes catalyzing oxidative phosphorylation. I. Purification and properties of soluble dinitrophenol-stimulated adenosine triphosphatase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 235 (11): 3322–3329. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(20)81361-1. PMID 13738472. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- ^ Boyer PD, Cross RL, Momsen W (October 1973). "A new concept for energy coupling in oxidative phosphorylation based on a molecular explanation of the oxygen exchange reactions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 70 (10): 2837–2839. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.2837B. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.10.2837. PMC 427120. PMID 4517936.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1997". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

Further reading

[edit]Introductory

[edit]- Nelson DL, Cox MM (2004). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- Schneider ED, Sagan D (2006). Into the Cool: Energy Flow, Thermodynamics and Life (1st ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-73937-6.

- Lane N (2006). Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life (1st ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-920564-7.

Advanced

[edit]- Nicholls DG, Ferguson SJ (2002). Bioenergetics 3 (1st ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-518121-3.

- Haynie D (2001). Biological Thermodynamics (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79549-4.

- Rajan SS (2003). Introduction to Bioenergetics (1st ed.). Anmol. ISBN 81-261-1364-2.

- Wikstrom M, ed. (2005). Biophysical and Structural Aspects of Bioenergetics (1st ed.). Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 0-85404-346-2.

General resources

[edit]- Animated diagrams illustrating oxidative phosphorylation Wiley and Co Concepts in Biochemistry

- On-line biophysics lectures Archived 2009-05-02 at the Wayback Machine Antony Crofts, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign

- ATP Synthase Graham Johnson

Structural resources

[edit]- PDB molecule of the month:

- ATP synthase Archived 2020-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Cytochrome c Archived 2020-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Cytochrome c oxidase Archived 2020-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Interactive molecular models at Universidade Fernando Pessoa:

![{\displaystyle {\ce {O2->[{\ce {e^{-}}}]{\underset {Superoxide}{O2^{\underline {\bullet }}}}->[{\ce {e^{-}}}]{\underset {Peroxide}{O2^{2-}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a3d9bf9d3a61736aa6207fa53b8ce0165b9eebb6)